Products You May Like

Editor’s note: In celebration of Golf Digest’s 70th anniversary, we’re revisiting the best literature and journalism we’ve ever published. Catch up on earlier installments.

Even today, long after this story was published in July 1998, Mac O’Grady is still referred to on our staff as the Great White Whale—an obsession that we chase but are unlikely to attain. He played the PGA Tour in the 1970s and ’80s after a record number of attempts at qualifying school, won two tour events, toyed with the idea of playing right-handed professionally and left-handed as an amateur, once attempted to play in a team event as his own partner, before finally settling into a career as a mysteriously reclusive teaching professional with a cult following. Golf Digest ranked him perennially among America’s 50 Greatest Teachers despite no cooperation and threats that he would banish any fellow teachers who gave us information about him. The names of his current disciples are withheld here to protect their access, some of them only knowing his teachings through bootlegged videos. Decades ago, he began work on golf-swing research that he called the MORAD Project, promising to publish the conclusions, but it remains elusive.

This story by Golf Digest contributor Kevin Cook won first prize in the Golf Writers Association of America writing contest, but it was strongly repudiated by O’Grady. In a letter to the editor at the time, he wrote: “The system cannibalized me over a decade ago. There’s no more flesh to eat. A fossilized carcass is all that remains. Don’t they realize I’m ancient history? My bones and career petrified long ago. DNA too, but never my spirit!”

O’Grady, 69, remains a cross between the Ben Hogan and Bobby Fischer of golf teachers—an apparition still sought by gurus and students of the game. We understand he divides his time between Palm Spring and Japan, but Golf Digest has stopped ranking him among the nation’s top teachers because we couldn’t verify whether he gives lessons anymore. The chase goes on.

“Hey, Mac! You’re tied for the lead.”

Mac O’Grady was winning the U.S. Open. In 1987, he made a final-round charge to catch Tom Watson, Scott Simpson and Seve Ballesteros at San Francisco’s Olympic Club. For about one minute, O’Grady was the hottest player in golf. Then a fan shouted the score. Mac hesitated. He paused to think back on the strange trip that led him to this moment. The PGA Tour’s leading flake, with a busted eardrum and 16 belly flops at Q school, was suddenly leading the Open.

O’Grady stood on the 15th green and wept.

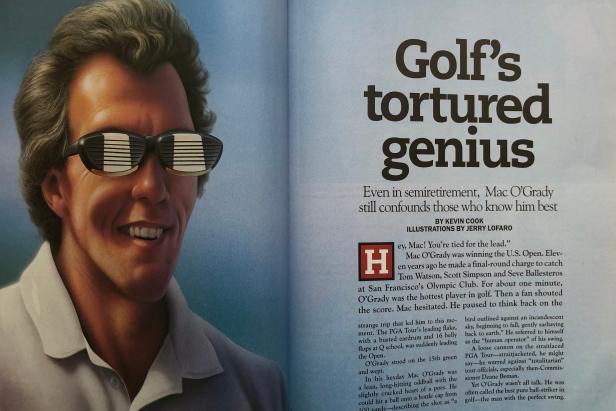

In his heyday, Mac O’Grady was a lean, long-hitting oddball with the slightly cracked heart of a poet. He could hit a ball onto a bottle cap from 100 yards—describing the shot as “a bird outlined against an incandescent sky, beginning to fall, gently sashaying back to earth.” He referred to himself as the “human operator” of his swing.

A loose cannon on the straitlaced PGA Tour—straitjacketed, he might say—he warred against “totalitarian” tour officials, especially then-commissioner Deane Beman.

Yet O’Grady wasn’t all talk. He was often called the best pure ball-striker in golf—the man with the perfect swing. Ben Crenshaw said O’Grady was hitting “some of the best shots ever seen on our tour.” O’Grady won more than $1 million on tour and had two victories: the 1986 Hartford Open and the ’87 Tournament of Champions. Then his twitchy putter and various injuries, including a chronically bad back, sent him into semiretirement.

He is seldom seen on tour these days, but his grating voice is still heard. A year never passes without a new O’Grady controversy. Last year he nearly got into a fistfight with another player while trying to qualify for the U.S. Open.

O’Grady lives with his wife, Fumiko, in a little condo in Palm Springs and teaches his theory of the swing to a chosen few “Macolytes” from whom he demands total loyalty. In the late 1980s, several of the world’s top-25 players were his disciples. Since then, he has been eclipsed as a swing guru by David Leadbetter and Butch Harmon, but that’s partly by choice: Mac says he abhors self-promotion, preferring a pure pursuit of golf perfection. He has spent more than $150,000 of his money on his long-awaited “MORAD project,” a computerized attempt to devise an ideal swing—to crack the game’s code (see accompanying story).

Even his friends call him “Wacko.”

Who is Mac O’Grady? Merely a fellow who “respects the game,” as he frequently insists? If so, he has odd ways of paying his respects. Isn’t this the guy who gets kicked off golf courses for his crazy stunts? Who once smacked an innocent tree with a baseball bat? Isn’t he infamous for blasting Beman, Ballesteros and Tiger Woods, and announcing that many tour pros are on drugs?

In fact, “Mad Mac” has always used golf as his private psychodrama. Often called a tour gadfly, he is entomologically closer to a killer bee with its constant buzz and hair-trigger temper, or perhaps a bombardier beetle, the bug that turns its back on enemies to spray them with venom.

Yet those enemies still call him one of the game’s great characters. And they admit that for all his quirks, O’Grady is still an artist when it comes to swinging the club. Such sweet swingers are often compared to Rembrandt, but Mac is no Rembrandt. He is golf’s van Gogh.

I spent three months getting to know his friends, enemies and siblings. O’Grady refused to be interviewed, though he allowed a friend to relay some of his views to me. Eventually I learned a lot about Mac, as well as another fascinating fellow he has long claimed dead, a self-made orphan named Phil McGleno.

Mac O’Grady was born Phillip John McGleno in Minneapolis on April 26, 1951. “Little Philly,” as the family called him, was beset by lung infections, always fighting for breath. He and his twin sister, Patsy, were the youngest of seven McGleno kids. They lived in Minnesota, Arizona and finally Los Angeles as their father, Phillip, an engineer, chased work.

The patriarch was cruel. He hit his kids. Violence trickled down to the youngest in the McGleno’s cramped apartment. Young Philly’s brothers beat him badly enough to bust his nose and damage his eardrums. One brother, a drug dealer, died young.

Philly grew strong enough to quarterback the football team at L.A.’s Hamilton High. Still, he doted on his mother until her sudden death after a cerebral aneurysm, when he was 16. That’s when his world unraveled. Only months later, his father brought a new wife home, a woman he had met at the funeral. “That’s what broke us up,” brother Terry recalls. “Philly just took off. He ran.”

His running became legendary. Phil McGleno was the original crazed jogger of Southern California. He often ran from L.A.’s Rancho Park municipal course to the ocean and back—a 14-mile roundtrip. He once jogged 110 miles to San Diego. Philly was also the best teen golfer at Rancho, where he turned up every day dressed in shorts, tank top and a cowboy hat, lugging secondhand clubs. He was a kid who muttered to himself as he hit a drive and a 6-iron into the par 5s, then three-putted for par. He never could putt.

One day Raphael Shapiro, a restaurateur who happened to be paired with McGleno, asked him where he lived. No answer. “He seemed embarrassed,” Shapiro says. At last, Philly admitted he was homeless. Sometimes he slept in the archway of the Catholic church where his mother had attended Mass.

“I took pity on him,” Shapiro says. He took Philly in, treating him to meals at Raphael’s Caesar Salad, where the boy ate three eponymous entrees, three servings of chicken parmigiana and a heaping plate of pasta. Shapiro learned McGleno had also been sleeping in a storage bin in Westwood, a nest feathered with blankets and carpet scraps.

At night, young McGleno ran a reading lamp off a battery. He perused Kahlil Gibran, wrote poetry (“Forever is a friend who comforts the heart full of woes”) and re-read The Golfing Machine by Homer Kelley, an obscure instructional tome, until he knew every line by heart. At dawn he would throw his golf bag over his shoulder and bicycle to exclusive clubs like Bel-Air and Hillcrest, where he’d hop the fence and sneak on.

The restaurateur also took his prodigy to experts like local pro Walter Keller, a golf-shop owner who loved what he saw. Keller’s student Amy Alcott would go on to LPGA greatness with 29 victories, but Keller saw more promise in McGleno.

“That boy could do anything. I got him when he was 19. Gave him shoes and golf balls, dressed him right out of my shop. He coulda been on tour at 21. He coulda been the greatest trick-shot artist ever,” Keller says. He shakes his head. “But he was stubborn.”

Keller arranged playing privileges at Riviera and other premier venues, but the kid alienated everyone with his loud opinions and fiery gaze. “I’m already a pro,” he boasted.

Riviera regulars Dean Martin and Glen Campbell briefly backed him, but the crooners soon stopped sending checks. Keller was convinced he was uncoachable. McGleno was certain he knew the swing better than Keller did. When Keller and some friends leased a car for him—with the stipulation that he not leave California—he promptly lit out for a betting match in Texas. Even as a pauper, he acted like a prince.

But the prince was a putz with the putter. His enemies, who soon included Keller and other backers who tried to tame him—“avaricious sharks,” he would call them—had an easy excuse for dismissing his chances. Phil McGleno never met a three-footer he couldn’t miss. Worse still, his putting woes doubled when the stakes increased.

“Every year I rounded up the money to send him to qualifying school. He’d miss by one stroke, two strokes,” Shapiro says. Starting in 1971, McGleno flunked Q school 16 times in a row, a record of futility that might stand forever. His frustrated patrons also bankrolled his efforts on the Asian and European tours. Still he failed, missing too many crucial putts. His caddies whispered he was a choker.

“He thought too much,” a friend says. “One day he swings like Nicklaus, next day Trevino. That’s how he went from a 16-year-old who hit it 300 yards to a 20-year-old who couldn’t hit it 220.”

Yet he swore he was destined for greatness. And his talent made people believe. In a local match against Gary McCord, McGleno was stymied under a tree. He grabbed his secret weapon, a left-handed 7-iron, and hit a 150-yard beauty ambidextrously. He won the match. Another time he shot 62 right-handed, then turned around and shot 69 lefty.

For a time he lived with his twin sister, Patsy, the one relative he could tolerate, who by then was married and living near Los Angeles. Such comfort couldn’t last. By then, homelessness was old hat for McGleno. He had worked and bunked at the Westwood cemetery where Marilyn Monroe is entombed. Ex-quarterback Phil tossed a football with a co-worker there; one pass pattern was called “Slant Toward Marilyn.”

Sometimes he bused tables at Shapiro’s new restaurant in Palm Springs, but he was homeless again when he returned to L.A. in 1978 and nearly died of pneumonia. In desperation, he called a Japanese woman he had met at Rancho Park. Fumiko Aoyagi, who ran the Hermès store in Beverly Hills, took in the wild-eyed chatterbox and nursed him to health. Soon they were married. But Fumiko did not become Mrs. McLeno, for her “Phillip-san” had gotten a new name shortly after they met.

With Shapiro at his side, the 26-year-old McGleno entered the Palm Springs courthouse and emerged as Mac O’Grady. O’Grady was his mother’s maiden name. “Phillip McGleno is dead,” he said.

Was he referring, at least in part, to Phillip McGleno, his hated father, as well as to himself? Years later, when Mac learned from his twin that their father was dying, he laughed.

In 1981 came his worst golfing heartbreak. At his 16th Q-school tournament, he led the field after 36 holes only to suffer a history-making meltdown. He shot 80 in the third round, 80 in the fourth round.

Of course, being Mac O’Grady, he had another surprise in store. The next year at the Tournament Players Club in Ponte Vedra Beach, he was brilliant all week. Rolling in putts from all over, he finished tied for fourth there, at his 17th Q school, earning $6,000 and a ticket to the PGA Tour. “Big Mac is in the Big-Big Leagues,” he wrote in a note to himself. His old life was over, and he knew it.

“I had a few cocktails that night,” says McCord, who earned his tour card that same day. “I asked Mac to come along, but he said he had something to do.” That evening, O’Grady carried 16 baseball bats onto the TPC course. On each one, written in Magic Marker, was the date and site of all 16 of his Q-school failures. Mac took aim at a tree. He proceeded to swing full force at the tree until each bat was shattered.

In 1983, O’Grady, 31, was the PGA Tour’s oldest rookie. Still, even after a decade of trying to join, he skipped the tour’s first event. He passed on the Tucson Open to make his debut at the L.A. Open played at Rancho Park, his old home turf.

Sentimental? “You don’t know,” Shapiro tells me. “Have you been to Rancho? The clubhouse is on Patricia Avenue. His mother’s name.”

In his first years on tour, O’Grady became affluent beyond his dreams. “Dial-a-shot O’Grady,” Johnny Miller called him. Mac sank enough putts to earn $223,808 in 1985, good for 20th place on the money list.

“I have moved from the prodigy stage to virtuoso,” he crowed. But he cared little for money. If he won $10,000, he’d give his caddie the usual 10 percent plus a $500 tip. He refused all endorsements and took no money from his students, a fast-growing corps of golfers that believed Mac was a genius.

As his reputation spread, other pros as well as celebrity amateurs came calling. His celeb list featured Lee Iacocca, singer Vic Damone, baseball Hall of Famer Johnny Bench and casino mogul Steve Wynn. O’Grady refused their money. Damone and Vijay Singh provided him with cars to replace the rusty blue ’72 Chevy he rattled around in. But Mac the golf guru barely drove the Rolls-Royce that Damone gave him to use. O’Grady was on a quest to teach others the mechanics and spirit of the perfect swing—his swing.

McCord recalls the day Gene Littler drove to O’Grady’s local muny seeking Mac’s unique assistance. When Littler pulled up in his Rolls-Royce, O’Grady was waiting with a swivel chair and two bottles of wine. He proceeded to demonstrate the principle of centrifugal force on the 66-year-old Littler.

“He sits Gene in the chair. Hands him the bottles of wine, tells him to hold them close to his chest,” says McCord. “Then Mac says, ‘Hang on,’ and he starts spinning him. Littler’s going round and round, and I’m sure the poor man is going to throw up. Mac says, ‘Stick your arms out!’ And Littler slows down. ‘Pull ’em in!’ He speeds up. I am watching Gene Littler get spun by a madman.”

O’Grady wrote to NASA volunteering his services to the space program. He applied to the 1985 Chrysler Team Invitational as his own switch-hitting partner—a lefty-righty one-man team. In an attempt to learn patience, he drove around Palm Springs at a snail’s pace, following elderly motorists.

O’Grady’s reputation as the tour’s best pure ball-striker was growing, but Mac couldn’t crack the winner’s circle. After blowing a Sunday lead at the ’86 Canadian Open, he wrote a note to the game: “Dear Mrs. Golf. I hate you.”

Again he bounced straight from hate to elation. The next week at Hartford, he shot 62 on Sunday, then beat a surprised Roger Maltbie in a sudden-death playoff. O’Grady won $126,000 and dedicated his first victory to “dreamers—people whose spirits never fragmented along the yellow-brick road.”

Reporters looked puzzled. A few laughed. Mac was earning a name as the tour’s top quipster. Few knew that he wasn’t joking—that he is, in fact, almost humorless, a self-taught dropout who loved using $10 words to prove he was smart. When he regaled the press with talk of “proprioception” “vestibular-ocular response” and “the metaphysical heebie-jeebies,” he was serious.

In ’86, he began a public war with Beman, the commissioner. A volunteer at the New Orleans tournament claimed O’Grady had called her a bitch, a charge he hotly denied. Beman assessed a token $500 fine. O’Grady refused to pay. The tour deducted the $500 from one of his paychecks, and Mac went berserk. He called Beman a thief. He publicly compared the commissioner to Hitler. So Beman upped the fine to $5,000 plus a six-week suspension, the harshest penalty of his 22-year reign as the commissioner.

Had O’Grady apologized then, he might have escaped by paying the original fine, which amounted to a caddie’s tip. Instead, he sued the tour. “It was Mac v. Authority, his favorite fight. That’s his soup. He wants a father to defy. I think that’s what happened with Deane,” McCord says. “Someone in authority said, ‘No, you can’t do that,’ and Mac said, ‘Watch me,’ ”

The scandal ended with a whimper. While dismissing O’Grady’s lawsuit against Beman and the tour, a Federal judge scolded the plaintiff: “Mr. O’Grady would better serve himself by polishing his clubs and his golfing skills … and leave off his temptation for verbal engagements.” In the end, O’Grady paid the $5,000 fine.

O’Grady’s last victory came at the ’87 Tournament of Champions at La Costa, where he edged Mark Calcavecchia, Rick Fehr and Greg Norman. The heebie-jeebies chased him on Sunday; on the final nine holes, he three-putted from eight feet, then again from 14 feet. “I thought if I touched the ball it would explode like a hand grenade,” he said later. “The demons come out. You have got both feet in the grave.” But after ramming home a 48-footer on the 14th hole, he was a winner again, hugging a jubilant Fumiko.

Reporters laughed at Mac’s calling his putter a victim of “focal dystonia.” But he was being honest. Then 35 years old, he was a chronic victim of the yips.

Soon he would attack the problem in his own way, paying for a $30,000 study by UCLA’s medical department. The results, published in the journal of Neurology, found the yips associated with three factors: advancing age, obsessional thinking and how long the subjects had played golf. Thus he was perfectly serious in saying, “The nerve endings in my fingertips were misfiring.”

One fan at La Costa that grand day was Mac’s sister, Patsy. Mac gave her his glove as a souvenir. On the way home, she found a $1,000 check tucked inside.

Mac and Fumiko made a nest of their own in Palm Springs, in a modest condominium full of his books and charts and an anatomical skeleton on a hook. Friends say Mac was frantic in 1992 when Fumiko was told she had breast cancer, and never more joyous than when she recovered. Fate had, for once, smiled.

By then O’Grady seldom played on tour. Bedeviled by severe back trouble that he might have worsened with his long daily runs—seven-mile sojourns in the mountains, through elevation changes of nearly a mile, often in 110-degree heat—Mac was forced into a kind of retirement, which he made with the usual parting shots. He announced he was glad to be finished with golf’s “tin-can bureaucrats” and “dumb, ignorant jockocracy.”

But O’Grady never really disappeared, even while insisting that he didn’t miss competing. He played nine tour events in 1997 and made but one cut. His $3,078 paycheck for finishing tied for 51st at the B.C. Open was the sum total of his tour earnings that year. Still, it nearly matched the $3,949 he earned in 1994, ’95 and ’96 combined. His career earnings crept up to $1,047,259.

“He still liked performing for people, though,” Shapiro says. “He’d get Fumiko and me to listen on the speaker-phone when he called important people.” On one such call, Steve Wynn, who often gave O’Grady free lodging and the use of a private plane, urged Mac to stop annoying everyone in golf with his big mouth. Shouting his refusal, Mac hung up.

O’Grady seems to be comfortable in the midst of warfare. He made news at the ’94 Masters by announcing that “at least seven of the top 30 players in the world” used drugs. He said they took beta blockers to steady their nerves. Beta blockers are prescription blood-pressure drugs that can act as tranquilizers; O’Grady admitted using them himself—experimentally—and said they once helped him beat Tom Watson in a match-play event.

When O’Grady’s accusations became public, Norman, Raymond Floyd and other players instantly called for Mac’s ejection from the game.

O’Grady knew how he was being perceived. He said at the time that he didn’t want to be “labeled as the perpetual martyr and heretic and nonconformist and extremist of this tour. I respect the game.”

He told Beman that his sense of honor demanded a formal inquiry into beta-blocker abuse. His sense of honor might really just be a showy sense of outrage. Why else would he suddenly start ripping Tiger and Earl Woods during the Ryder Cup—and providing the tabloids with ripe material? How else to explain his behavior at a 1997 U.S. Open qualifier in Borrego Springs, Calif.? Incensed by what he deemed to be poor etiquette of playing partner Graeme Reid, a part-time pro golfer, O’Grady allegedly challenged Reid to a fight. He challenged the wrong man. Reid, a San Diego lawyer, sent copies of a furious letter to United States Golf Association and PGA Tour authorities, citing O’Grady’s behavior.

O’Grady is simply at home when out on the lonesome edge. During his public fight with Beman, Mac went on the David Letterman show. Naïvely expecting their chat would be spontaneous, he was annoyed when a producer tried to prepare him and tell him what to say. The producer made the mistake of adding that Letterman dislikes physical contact. That night O’Grady kept patting and squeezing Letterman’s leg to the host’s clear discomfort. Mac later bragged about it—how he’d psyched out David Letterman.

O’Grady cuts off friends and students with scary regularity. Many people contacted for this article asked not to be quoted by name. Why? “Mac’ll kill me.”

Latest to be cut off is tour pro Grant Waite. Waite is uneasy discussing O’Grady. He says only that he violated one of Mac’s many rules. Before last winter, they often went to tournaments together. They spent 13 hours a day together, from breakfast to range time; through the round, when O’Grady would walk outside the ropes; through longs talks over dinner. It was a commitment that grew heavier with time.

“I have a life, a family and other friends I cannot sacrifice,” Waite says. He felt stung when O’Grady erased him from the inner circle, but Waite still praises Mac’s better qualities: “When you interact with such intelligence and passion, you can’t help being affected.”

Like others who know O’Grady, Waite considers him a genius but suspects he lacks a certain golf instinct—whatever mojo it is that allows a Nicklaus or Tiger Woods to forget all he knows of swing mechanics and just hit it. With the ball on the tee on Sunday, such men have that one overriding thought, while O’Grady weighs 187,200 variables.

“Understanding the swing and understanding how to play may be two different things,” Waite says.

O’Grady temporarily cut off lifelong pal McCord for speaking to David Frost—a student of David Leadbetter, whom O’Grady mistrusted and accused of stealing his ideas. It was as sudden a freeze as the time when past student Jodie Mudd got cut off after he thanked Beman on TV. Boom. Gone.

Even Ballesteros was frozen out for fraternizing with enemies. How bitter was the O’Grady-Ballesteros spat? O’Grady called Seve “emotionally bankrupt” and said he would never be good again. “Seve is a collapsed star, a black hole.”

When pressed for the real reason they split, O’Grady told the Los Angeles Times: “I finally found someone more neurotic than me.”

Even Shapiro was cut off dead. His crime was running late chauffeuring Fumiko home from the airport. “He said, ‘I won’t need you anymore,’ ” Shapiro recalls. “After 20 years! I bankroll my life on this guy, and he screws me. He won’t talk to me.” A bitter Shapiro is writing a book he calls The Rise and Fall of a Potential Golfing Superstar.

There’s no danger O’Grady will run out of followers. His allure as a guru is mythic, almost hypnotic.

McCord recalls the first lesson he took from Mac. It lasted 10 hours. O’Grady eliminated excess motion at a dozen points in McCord’s swing. “All of a sudden my swing got real tight,” McCord says.

Mac gives his disciples demonstrations they never forget. He has students roll balls at him and hits them on the run, yelling “Hook” or “Fade” before sending them off on various trajectories. A pro who fell under his spell watched one of O’Grady’s favorite tricks. Mac dropped a ball on a sidewalk, pointed to a bathroom door 100 yards away and hit a screaming 3-wood through the door. “And I mean through the door,” says the pro. “A veneer door, and he knocked a hole in it.”

For all his talent as a player, O’Grady never quite fit the role. He was the only tour pro who would miss a plane to watch a great sunset.

“I’d say Mac did well for a guy who really couldn’t putt at all,” McCord says. “He was never a great wedge player, either—he was so powerful, he couldn’t slow the club down. But for Mac, playing the game is not what’s important. His quest means more than trying to make five-footers go in. Mac is on an information siege. He wants to make the swing give up its secrets.”

Since 1990, pros have been able to find O’Grady teaching out of Thunderbird Country Club in Palm Springs. Club pro Don Callahan, who convinced Thunderbird’s board of directors to let O’Grady set up shop there as a quasi-official teaching pro, lauds Mac’s “honesty, integrity and manners.”

Today, O’Grady spends time refining The Model. He teaches, sometimes on a shaggy public range where no one else knows a slice from a fade. As for his now-shrinking posse, O’Grady is in eclipse.

“He knows he’s not talked about so much anymore,” says a friend. “He’d give anything to have one of us, his guys, win the Masters or the U.S. Open.”

Worry about his fading reputation might be making him quirkier than ever. In recent years, as Leadbetter’s students prospered, O’Grady has tightened the screws on his own cultists.

“You can’t talk to a Leadbetter guy. You can’t teach people he doesn’t like, or he puts you on probation,” says one. “Then you have to give back all the computer printouts of your swing in all the positions. You can’t say the word MORAD or swing his way for 30 days.”

To know O’Grady, picture one of his favorite drills. You are lying down 20 feet in front of him as he hits 1-iron shots over your shoulders. More than a test of his skill, it’s a test of your trust in him.

“Older but still has not grown up.” That’s how he signed a card to Patsy on their birthday. He would not grow up, not if it meant letting go of the past, his grudge.

“It was the death. You have to understand Philly—to him, his mother was everything,” Patsy says. After their mother’s death, Patsy was the only McGleno whom Philly could love. Ten years later, when she had her first child, Mac sent her a card with a heartfelt note at the bottom, his dreamy evocation of the infant’s “tiny eyes and starfish hands.” He signed the note Phillip O’Grady.

“I put it behind me. I have to sleep at night,” she says. “But Philly never could. He could never forgive and go on.”

Last winter O’Grady sent word that he would not talk to me. I learned he was mad at the magazine. In May 1987, Golf Digest published a cover story about him. It was called “The Best Swing on Tour?” Various experts analyzed and praised the photos of O’Grady’s “symmetrical” left- and right-handed swings.

“Mac was furious,” recalls Dr. Francis Crinella, his ally in the MORAD experiment. Why? “Those photos were not perfect mirror images.” O’Grady’s neck was tilted in one photo, his feet slightly askew in another. And while no readers detected the difference, and even tour players were filled with admiration for it—Paul Azinger said the demonstration was “simply astounding”—O’Grady went ballistic.

“Most of us get edited. We don’t have full control of our lives. Mac isn’t like that. Mac will not be edited, he will not be coerced,” Crinella says.

Which explains why there is still no book, no instructional video from the great guru. “If Mac ever finished his work, he would have to let other people see it,” McCord says. “Then he wouldn’t be the only one who knew his secrets, would he?”

In January 1997, I knocked on O’Grady’s door. No answer. I paced Mac’s patio, a nondescript slab of cement with Astroturf and sunburned potted plants. The head of a 3-wood lay upside down beside one of the plants. A golf tee did padlock duty on the hinge of an outdoor storage bin.

“There was a lot of testosterone in the house we grew up in,” big brother Terry McGleno, now a Seattle construction contractor, told me. “There was teasing. There was hitting. I’m sure Philly got punched. I probably hit him—but as far as regular beatings, no.”

“His brothers beat him up, and he lost 60 percent of his hearing,” McCord says. “So I bought him a hearing aid. Mac hated it. He said he could hear every bird in the world. He could hear everyone talking. He threw it away.”

“He used to send me roses on our birthday,” says Patsy, their mother’s namesake. “I wish I could see him again.”

Before I left O’Grady’s Palm Springs patio, I looked for some detail to give me a better sense of him. And pacing around Mac’s place, violating his Astroturf, I noticed that his back porch faces the wide, green fairways of Canyon North Country Club. In fact, Mac’s porch is almost in play.

He lives two yards out-of-bounds.

MORAD: Mac’s mysterious swing secrets

Mac O’Grady’s lifework is the MORAD (for McCord O’Grady Research and Development) project, filled with all the information he has gathered on the golf swing over the years. Its central model is nothing less than the ideal swing, mathematically specified and charted in three dimensions.

Incredibly complex, the model features 10 segments, or ideal positions, from address to follow-through. Each segment has 10 subsections, each of which has a proper position for 13 body parts. Specified in three dimensions, that means 3,900 variables per swing. And you’ll find more refinements in O’Grady’s sheaves of charts: every variable optimized for each club; for hooks, draws, fades and slices; high, low and medium trajectories. The model contains precisely 187,200 variables, “and Mac knows them all,” says a doctor familiar with his work.

Dr. Francis Crinella, a neuropsychologist at the University at Irvine, says O’Grady’s eye “is like a high-speed camera connected to a computer.” Crinella, author of a book titled Brain Mechanisms, calls the high school graduate O’Grady (Mac briefly attended Santa Monica Junior College) a genius. “I believe Mac understands what happens during a golf swing as well as anyone. But he is never satisfied. He is always refining the model.”

O’Grady can assign a score to any swing. Davis Love III, for instance, gets about 92 out of a perfect 100. Former Macolytes like Chip Beck, Steve Elkington and Grant Waite score higher. Sam Snead’s swing is a near-perfect 99. “Mac is 100,” Dr. Crinella says.

Two questions remain of MORAD, locked away where only the highly suspicious and controlling O’Grady has the answers: Will it ever be published? And if so, will anyone be able to understand it?